At an exhibition of Dr. Max Liboiron’s work, you might be asked to purchase a tiny plastic home or better yet, build your own. And you might wonder if you’re participating in a science experiment or attending an art show. The truth is, you’re doing both.

Dr. Liboiron is an artist who also directs the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR) at Memorial University of Newfoundland. CLEAR develops feminist and anti-colonial methodologies and instruments in the natural sciences by grounding them in Indigenous thought and feminist social movements, creating place-based and ethical scientific protocols in marine plastic pollution research. Dr. Liboiron uses the materials discovered through the course of her research to create installations that challenge our previous understanding of plastics. In doing so, she creates spaces that offer alternatives to capitalism alongside the often unsettling opportunity to be intimate with the waste we have produced.

Dawson City Trash Project

CLEAR is described as a “feminist, anti-colonial laboratory that specializes in grassroots environmental monitoring of marine plastic pollution.” How does your personal lens influence your scientific research?

As feminist scientists, we build equity into our practices—the idea that people start from different social, economic, historical, and political positions and that the root of these differences should be acknowledged and addressed in all research, including science and art. In opposition to the notion that Western scientific rationality is the only valid scientific method, we make space for different ways of knowing in terms of knowledge production. Reflection time is built into our scientific protocols and this is where most of my recent work comes from.

Dinner Plates (Northern Fulmar)

To which extent do you see the practices and mentalities of pollution and colonialism as being interrelated? By deconstructing one, could the other also cease?

Colonialism refers to a system of domination that grants the colonizer access to land for their goals. This does not always mean property for settlement or water for extraction. But it can mean access to land-based cultural designs and cultural appropriation of symbols for fashion. It can mean access to Indigenous land for scientific research. It can also mean using land as a resource, which may generate pollution through pipelines, landfills, and recycling plants.

Colonialism makes land pollutable as a resource for colonial and settler goals, so an end to colonialism would mean an end to pollution as we know it. Would it mean an end to all pollution of all kinds for all time? Not likely.

New Stories: Aurora Borealis and the Melting Tundra

In pieces such as Eco-System and Dawson City Trash Project, you gave the viewer decision-making power about the destiny of the pieces. What did this teach you about the way economies are tied to the land and to personal possession?

When I ran Eco-System in different places, it had different results. In that project, the audience could spend $20 to either buy part of the installation or secure it so others couldn’t take it. The first place I showed it was on a resort island with a lot of private second homes. All were taken away, and the one that was preserved was by a visitor. That ratio changed to 50-50 in a university town and rural town.

In the Dawson City Trash Project, people could take anything at any time. It was wide open. People started to make their own rules, like that you could only take one thing, or that you should only take small things so as to not disturb the overall installation. Many locals chose not to take their piece until the end of the show, to ensure visitors would still get to see the entire installation.

For me, what this means is that non-capitalistic ways of making economic relations are already existing within the collective consciousness. There’s a saying that “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism,” but people consistently imagine alternatives to capitalism in nearly every show.

Eco System Detail

In Sea Globes you work with found objects from the New York area, which you refer to as “genuine New York souvenirs.” What did you learn from creating this series?

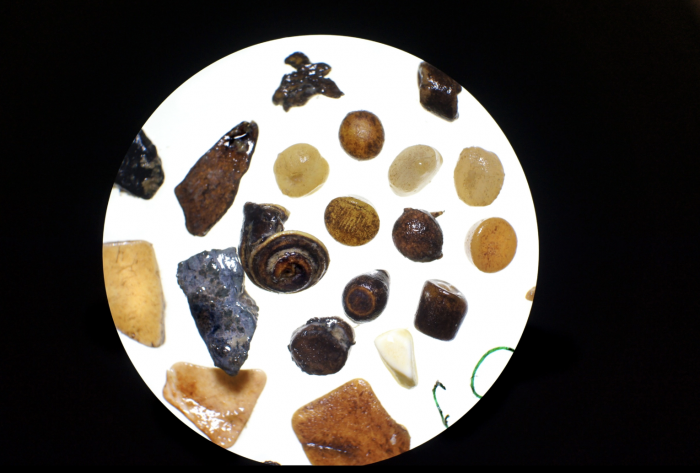

Working as a scientist, I’ve come to know that different waterways have different plastic profiles or plastic personalities, if you will. One of my first research trips was on the Hudson River. The water there is filthy, with more microbeads from personal care products than anywhere I’ve researched before. I learned that the tiny sparkles in toothpaste are made of plastic right on the Hudson. Plus we found plastic dime bags, which I have not found before or since. I had to teach part of the crew what they were. Plastic pollution has very specific local characteristics, that’s why it can become a place-based souvenir—it is unique to that place.

Small Sea Globes

As a diver, I often find plastics that have been absorbed into the landscape, whereby removing them would involve hurting the organisms that have made their home in and around them. Similarly, in Plastic Is Land, plastics are a part of the landscapes you create. How does this new reality affect the way you continue to perceive and use plastics?

When you follow the thread of plastics in the landscape it becomes harder and harder to demonize plastics as foreign invaders. I remember coming across a polyethylene rope snarl in the ocean with my science crew. When we lifted it up, we found it to be covered in mussels, barnacles, and biota, and you could see all the wee swimming organisms left behind in the water. If we want to keep ecosystems healthy, then removing the plastic snarl would have meant destroying an entire ecosystem—it was the middle of a cold ocean and there was nowhere else for the biota to go! I think we need to develop protocols and ethics around how to deal with pollution that is also land, that is also kin, that is also supporting ecosystems. That is the intention of my art and plastic activism, to influence the way industries and economies use, dispose, and perceive of plastic.

Current Project on Discard Studies – Photo by David Howells

To learn more about Dr. Liboiron’s research check out her links below. You may also learn more about how plastic is a function of colonialism in her recent article for Teen Vogue.

Website: https://maxliboiron.com/

Lab website: http://civiclaboratory.nl

Twitter: @MaxLiboiron

Author: Carola Dixon

Editor: Dena Silver