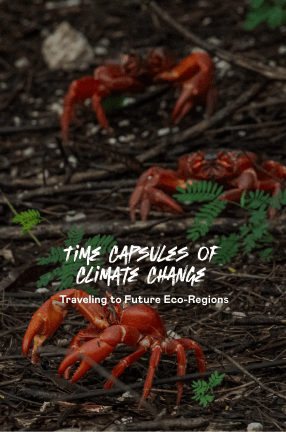

Time Capsules of Climate Change:

Traveling to Future Eco-Regions

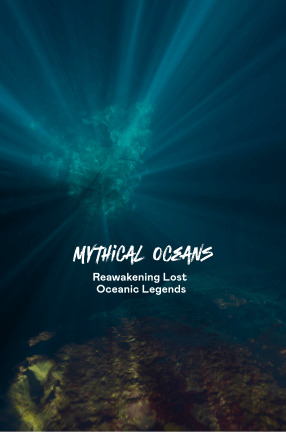

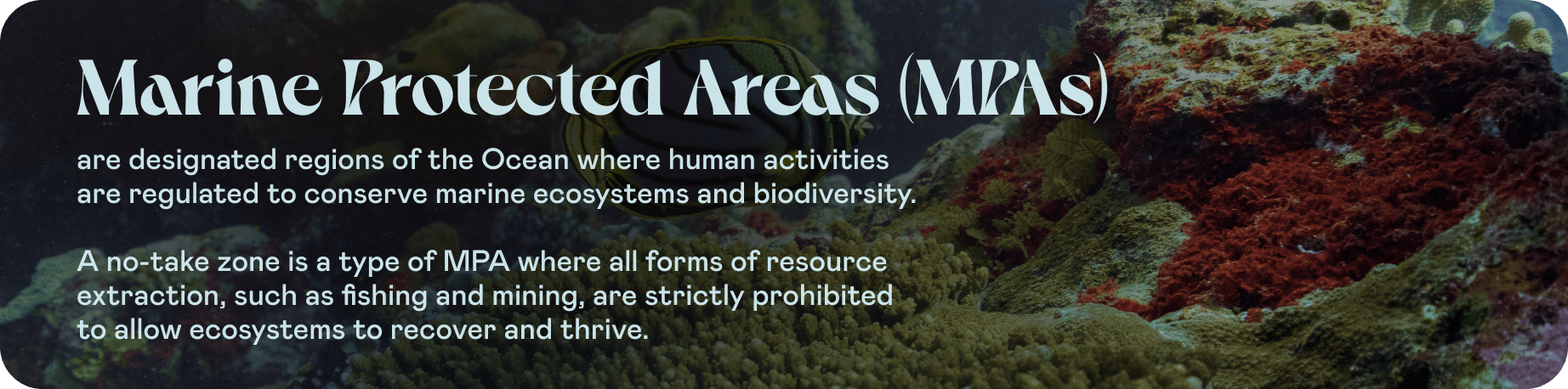

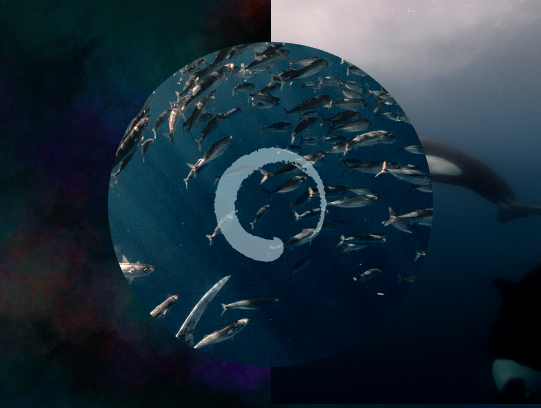

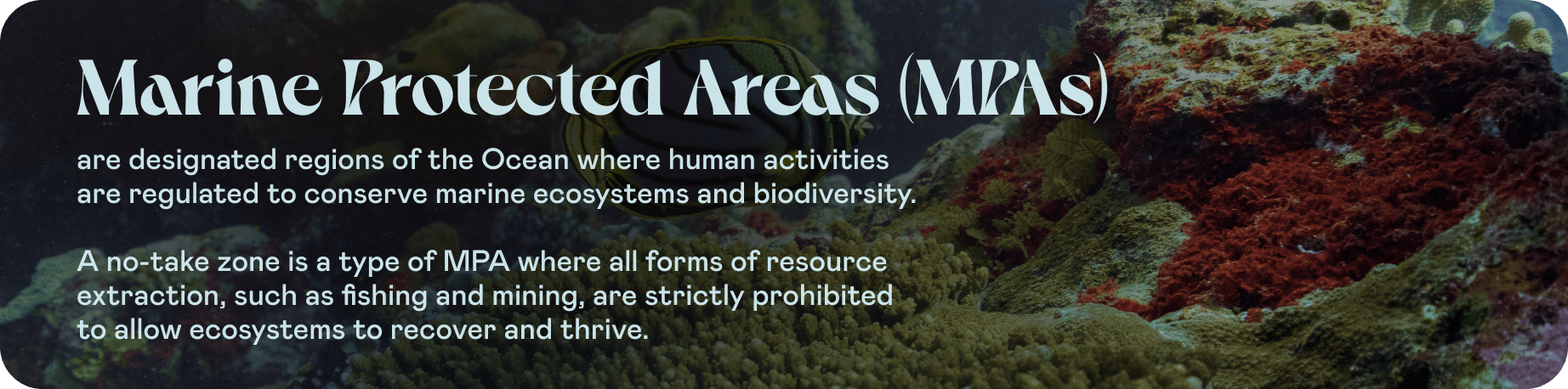

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are critical tools in the fight to conserve Ocean ecosystems, protect marine biodiversity, and sustain the livelihoods of communities that depend on the sea. Yet, the effectiveness of MPAs hinges not only on their designation but on how well they are managed and enforced. Creating a protected area is a significant first step, but it takes robust planning, resources, and long-term commitment from governments, scientists, and local communities to ensure these areas fulfill their potential. Globally, less than 3.5% of the Ocean is currently under some form of protection, and within that fraction, only a small percentage are no-take zones—where extraction and destruction are fully prohibited.

Working closely with Marine Conservation Institute, the Edges of Earth Expedition team has explored some of the most successful MPAs on the planet to better understand what makes them work. As pioneers in global marine conservation, Marine Conservation Institute is not only leading the charge in creating a worldwide system of highly protected Blue Parks but also maintaining the Marine Protection Atlas, the most comprehensive database of MPAs worldwide. The Blue Parks title has been awarded to some of the best managed and enforced MPAs like Chumbe Island in Zanzibar, Tanzania, and the Revillagigedo Archipelago off Mexico’s Baja California Sur—places that typify the potential of well-established and well-managed marine refuges.

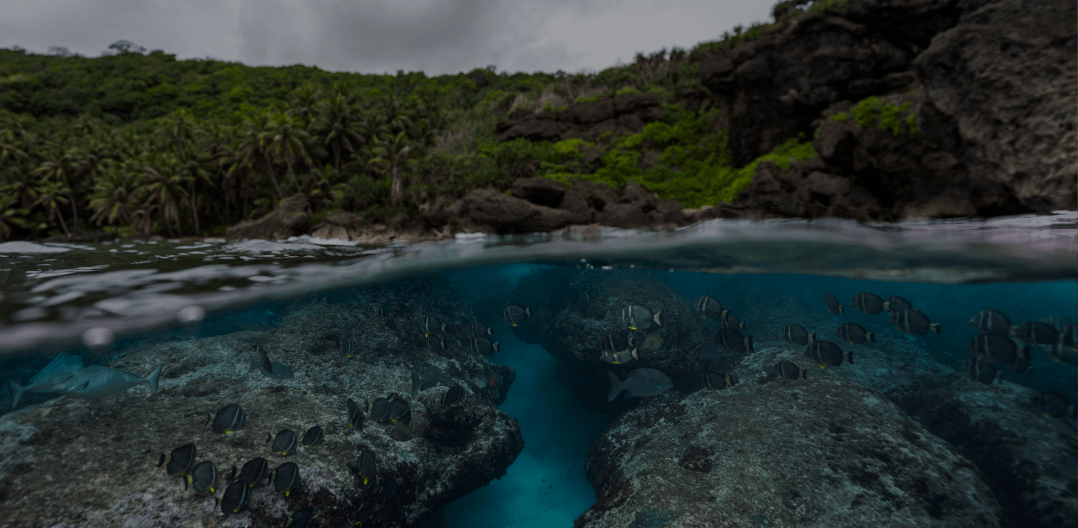

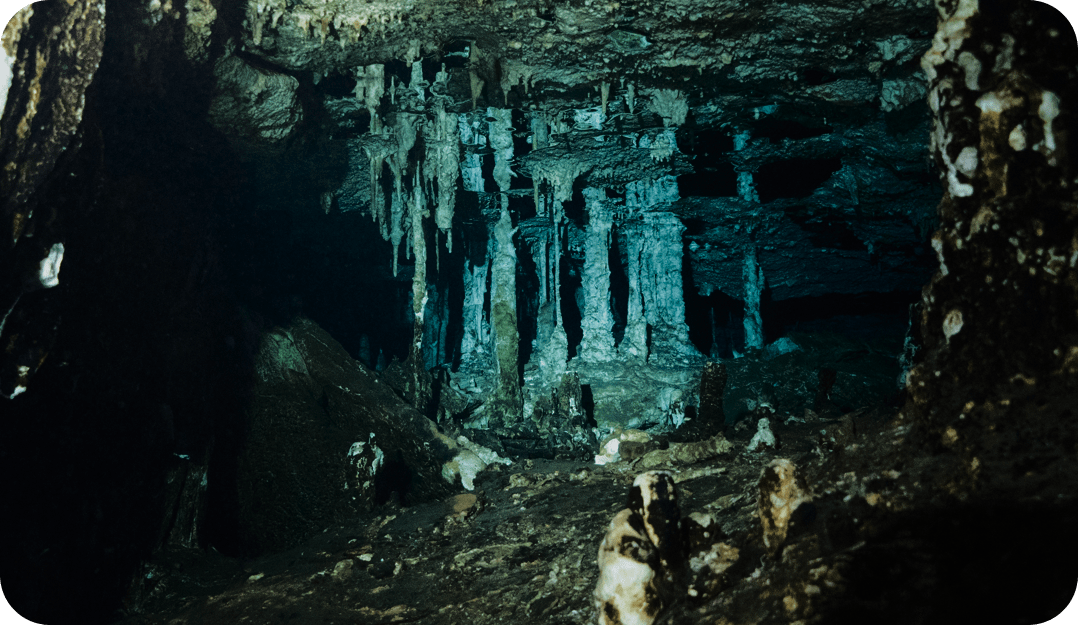

Diving Revillagigedo Archipelago’s Socorro Island. Photo Credit: Andi Cross

Throughout the journey around the world and back, Edges of Earth has also found emerging sites with immense potential to become future climate refuges. These up-and-coming areas are often at the heart of innovative research, grassroots conservation efforts, and community-led initiatives aimed at preserving biodiversity in the face of a changing planet. Recent travels have taken the team to places like the newly created marine park spanning Cocos and Christmas Islands, to the oyster restoration efforts happening in Scotland, and to the shark-tagging initiatives in La Paz, Mexico. Each of these sites represents a critical opportunity to expand marine conservation efforts globally and foster a sustainable future for the Ocean.

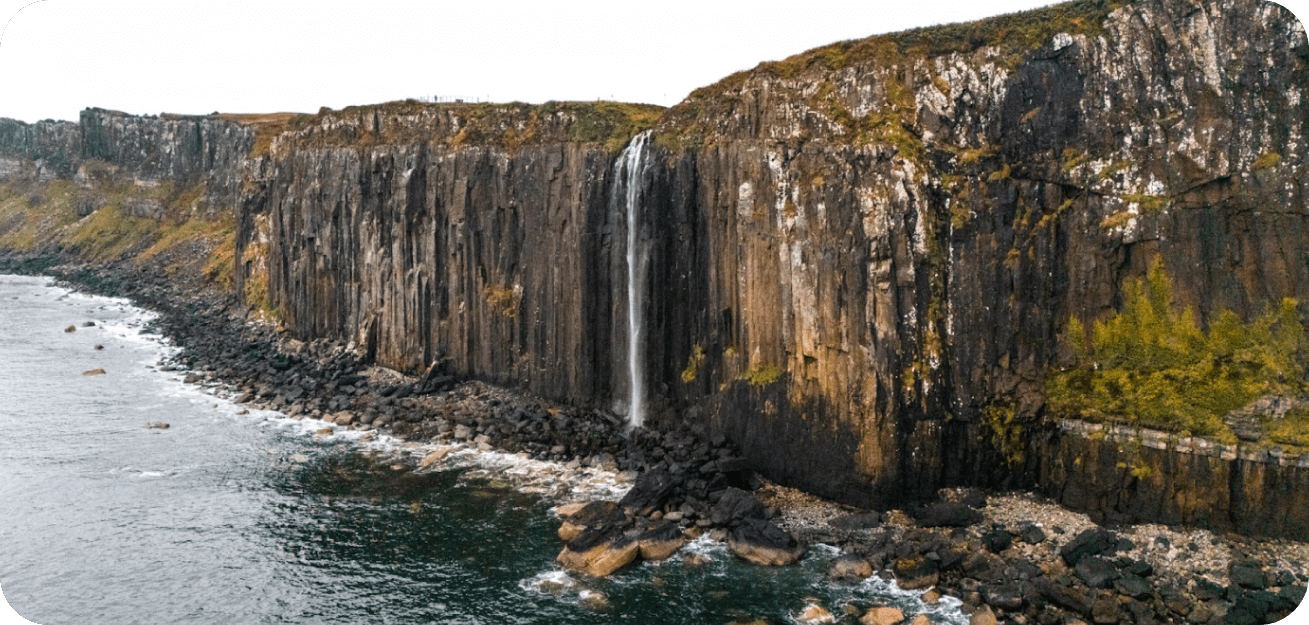

ARGYLL, SCOTLAND

Scotland’s landscapes, often shrouded in mist and steeped in a complex history of extraction, bear the marks of centuries of human activity. Once home to vast temperate rainforests and thriving marine ecosystems, much of its natural heritage has been lost to deforestation, farming, and overfishing. Native oyster beds, once abundant in Scotland’s waters, were harvested nearly to extinction, leaving a critical gap in the ecosystem. Yet, along the tranquil shores of Loch Melfort in Argyll, the Kilchoan Melfort Trust (KMT) is working to reverse this. Dedicated to rewilding and marine conservation, KMT is restoring Scotland’s ecological balance and transforming this corner of the country into a safe haven.

Oyster restoration work with Marnik Van Catuer of KMT. Photo Credit: Adam Moore

Central to KMT’s work is its oyster restoration program, which focuses on reintroducing the native European flat oyster. Unlike the fast-growing Pacific oysters common in today’s Scottish markets, these native oysters take years to mature but are essential to marine health, filtering up to 240 liters of water daily and creating habitats for diverse marine life. While living onsite at the remote estate, the expedition team saw firsthand how the oysters are raised in a “living laboratory,” nurtured in cages until they are strong enough to be released into historically significant locations. By rebuilding these shellfish reefs, the estate is restoring these lost populations, revitalizing ecosystems and creating long-term biodiversity hotspots. In just a few years, KMT has released over 50,000 oysters, offering a hopeful glimpse into how focused conservation efforts can heal damaged environments.

KMT is working to ensure their estate is a climate refuge. Photo Credit: Andi Cross

KMT is working to ensure their estate is a climate refuge. Photo Credit: Andi Cross

KMT has other climate resilience initiatives including seaweed farming, marine mapping, and species-based science. Collaborations with organizations like Tritonia Scientific enable the use of cutting-edge technologies to map seabeds and guide sustainable marine policies. Shark & Skate Scotland is another organization that allows KMT to better understand the critical marine biodiversity within Loch Melfort. This fusion of science and community-driven action positions KMT as a model for ecological restoration. By reconnecting with the region’s natural heritage, the trust is demonstrating how Scotland’s landscapes and seascapes can move from depleted to thriving, offering a blueprint for climate resilience.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND, AUSTRALIA

Learning about the newly established Cocos (Keeling) and Christmas Island Marine Parks, established only in 2022, the expedition team decided it was critical to head to what appears as no more than two tiny specs on the map between Indonesia and Australia. Together, these marine parks span over 744,000 square kilometers, offering protection to some of the Indian Ocean’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Christmas Island, with its steep drop-offs and nearly 75% coral cover, and Cocos, with its tranquil lagoon and 27 islands, face rising climate challenges. Among these is the preservation of the iconic red crabs of Christmas Island, whose migration is a spectacle of nature and a cornerstone of the island’s ecological balance.

Christmas Island is nearly all National Park. Photo Credit: Adam Moore

Every year, over 100 million red crabs embark on a remarkable migration from the dense island forests to the Ocean to spawn. Triggered by the first rains of the wet season, typically in October or November, this event is tightly tied to rainfall patterns and lunar cycles. Males lead the journey to the coast, digging burrows where mating takes place. The females then release tens of thousands of eggs into the Ocean during high tide, timed with the last quarter of the moon. The larvae spend weeks in the Ocean before metamorphosing into juvenile crabs and making their perilous journey back to the forest. This migration sustains the red crab population, while also fueling the marine ecosystem as well, as the eggs and larvae serve as a critical food source for fish and other marine species.

Christmas Island red crab getting ready for migration. Photo Credit: Adam Moore

However, climate change is disrupting this finely tuned process. Unpredictable rainfall patterns are delaying or interrupting the migration, leaving crabs vulnerable to dehydration and exhaustion. Without sufficient rain, the crabs struggle to complete their journey, and risk significant population losses. Changes in Ocean currents also threaten the survival of crab larvae, potentially sweeping them too far from the island or into areas densely populated by predators. Despite these challenges, innovative conservation efforts on the island, led by the Christmas Island National Park team, help safeguard the migration by reducing human-caused fatalities. This is just one of many of the park’s efforts to ensure the islands remain a climate refuge, while other initiatives focus on protecting coral reefs that rank among the healthiest in the world and monitoring key environmental indicators within the MPA.

Coral reefs of Christmas Island. Photo Credit: Adam Moore

Coral reefs of Christmas Island. Photo Credit: Adam Moore

At the heart of these initiatives is a community-driven approach, ensuring that conservation aligns with local needs and values. On Cocos, the marine park was established through extensive consultation with Cocos Malay, the native ethnic group of the island, in creating a management plan that reflects their ancestral connection to the sea. Similarly, on Christmas Island, efforts to restore balance in the forests and protect critical marine habitats are intertwined with the islanders’ livelihoods.

LA PAZ, MEXICO

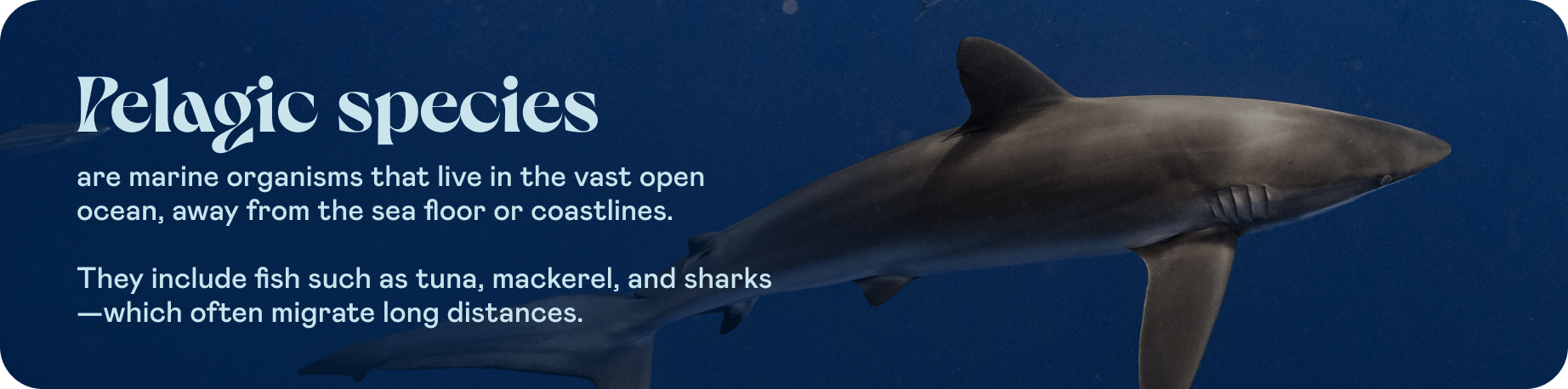

The Gulf of California, once hailed by Jacques Cousteau as the “aquarium of the world,” is a shadow of its former glory today. Decades of overfishing, industrial exploitation, and climate change have left its waters depleted, with species like hammerhead sharks and groupers now rare or absent. Yet, amidst these challenges, La Paz has become a hot spot on the conservation map, largely thanks to the work of Pelagios Kakunjá, led by Dr. James Ketchum.

Shark research with Dr. James Ketchum. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

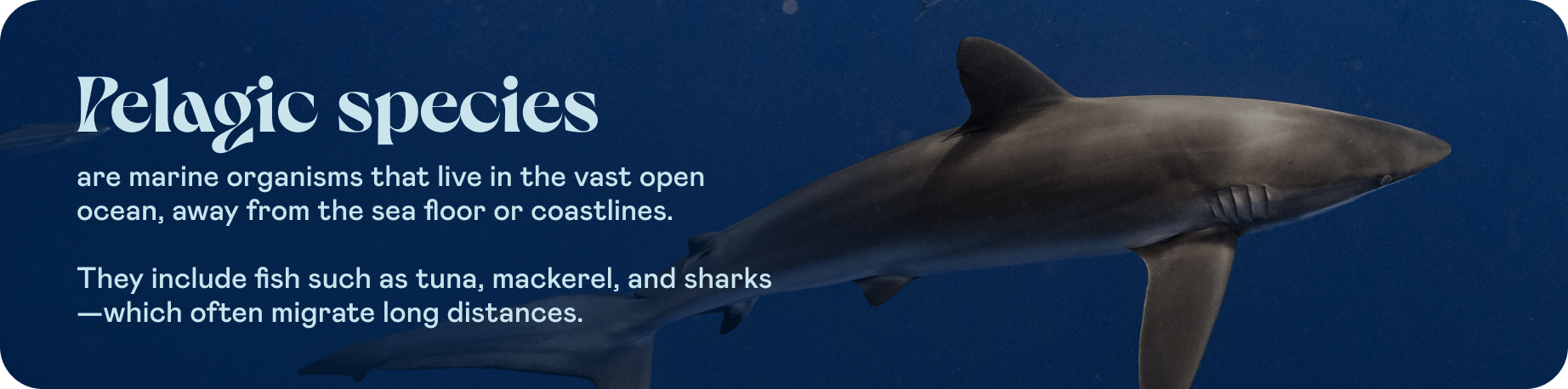

James has spent decades researching sharks, rays, and other pelagic species to inform conservation strategies and advocate for MPAs across the region. His work has already contributed to landmark successes, including the Whale Shark Refuge near La Paz and the expansive Revillagigedo Archipelago MPA. But now, he’s turning his focus to a new vision: creating a “migration corridor” that connects key marine hotspots, including Loreto National Park, Espiritu Santo National Park, and Cabo Pulmo National Park.

But this vision hinges on collaboration with local communities, particularly artisanal fishers who have relied on these waters for generations. Their traditional knowledge is invaluable for identifying critical habitats and designing MPAs that benefit both marine ecosystems and livelihoods. However, this balance is precarious. While many artisanal fishers employ sustainable methods like hook-and-line fishing, others have resorted to destructive practices like gill netting, exacerbating conditions for the already fragile fish populations. Industrial fishing poses an even greater threat, with large-scale operations depleting stocks and wielding outsized influence over fisheries management. James and his team of local fishers tag sharks to collect data off the shores of the remote Isla Partida to better understand how these sharks migrate to the next refuge in Mexico.

Dr. James Ketchum and his team. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

Dr. James Ketchum and his team. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

Climate change adds another layer of urgency to these efforts. Rising sea temperatures are driving species migrations, altering ecosystems, and causing the death of critical habitats like black corals and sea fans. Yet, through innovative tools like Global Fishing Watch and AI-driven data analysis, James and his team are identifying new conservation opportunities. As he puts it, the Gulf of California is at a crossroads: the choices made today will determine whether this marine haven can recover or continue its decline.

OJOCHAL, COSTA RICA

Then there’s Costa Rica— a place synonymous with ecotourism, a leader in terrestrial conservation that has protected 30% of its land through national parks and reserves. But its marine environments haven’t received the same attention. While 50% of Costa Rica’s waters technically fall into MPAs, less than 1% are fully implemented or actively managed. That gap inspired a visit to Ojochal, a small coastal village on the South Pacific side of the country where Innoceana, a local nonprofit, is working to establish a critical new MPA. This proposed zone would connect Parque Nacional Marino Ballena, Parque Nacional Corcovado, and Reserva Biológica Isla del Cano—creating an essential corridor for biodiversity and conservation.

Costa Rica is home to wild spaces and places. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

Innoceana runs science-focused expeditions, launching out of the SCP Corcovado Wilderness Lodge, an eco-partner of the nonprofits. From this remote base, Innoceana ventures to Cano Island, a national refuge moving with marine life. The waters surrounding the island are home to everything from hawksbill turtles to migratory whales passing through on their journeys from Alaska. Their work involves a wide variety of testing and studying, one of which is water quality monitoring. They focus on measuring the effects of agricultural runoff from nearby palm plantations—an issue that impacts both the marine ecosystem and local communities reliant on clean water. They also document the marine life passing through Cano Island’s sites, further bolstering the case for more MPA protection here, and throughout Costa Rica.

The Innoceana team out to sea. Photo Credit: Carlos Mallo

The Innoceana team out to sea. Photo Credit: Carlos Mallo

Cano Island is one of Costa Rica’s most biologically rich marine areas, yet it’s not fully protected as a marine park. The efforts of Innoceana and their partners aim to change that, ensuring the island and its surrounding waters receive the protection they urgently need. For travelers, this presents a unique opportunity: to engage directly in conservation through citizen science while experiencing some of the best scuba diving in Costa Rica. Tourism dollars spent on Innoceana’s expeditions directly support their work and the lodge’s sustainable initiatives. While Costa Rica has made huge strides over the decades, there’s still more work to be done—similar to many other hot spots around the world.

A BLUEPRINT FOR THE FUTURE

The stories from these emerging and established MPAs remind us that the fight for Ocean conservation is far from over—but also far from hopeless. From the red crabs of Christmas Island to the oyster reefs of Scotland, and from the shark corridors of Mexico to the biodiversity of Costa Rica, these regions offer a glimpse into what is possible when science, innovation, and community come together. They stand as time capsules of resilience, demonstrating the transformative power of local stewardship and global collaboration.

Diving Cano Island, Costa Rica with Innoceana. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

Diving Cano Island, Costa Rica with Innoceana. Photo Credit: Marla Tomorug

What lies ahead is a collective challenge: to protect and expand these blueprints for climate resilience while fostering sustainable relationships between humanity and the Ocean. The path forward requires urgent action, long-term commitment, and the recognition that every ecosystem, no matter how remote, is interconnected with the health of the planet. These places remind us of the Ocean’s boundless capacity for renewal—but only if given the chance.