Estabrak Al-Ansari is an award-winning Visual Artist & Film Maker, based between London, UK, and Muscat, Oman. She was born in Iraq, and raised in London, after having gone to the UK with her family as a child refugee.

Often lead by emotions, her art practice is shaped by a commitment to telling the stories of ignored socio-political realities. Using a variety of mediums such as photography, painting, and performance, her storytelling looks at the intersection between human relationships, identity, culture, and the environment. Since 2014, she has been attempting to understand these alternate realities through the lens of water, using the ocean’s motion as a means of representing environments and human behavior.

1. How does the ocean, and your relationship to it, shape you?

‘Like the legs of a bulb intersecting its way through the earth… We find our roots reaching out grasping at the water that holds us. Never caught, only held, we continue growing.’ Excerpt taken from the artists personal diaries during the production of Omanis Under Water

I find myself in the forgotten stories of the everyday. In water, I often seek comfort, truth, and answers. It is a place for listening in motion. Here I have found a way to have honest conversations, without pointing fingers, but rather inviting, through simple exchanges, those who are also interested in listening.

2. What space does art occupy in your life? How does it shape your experiences?

Growing up in a displaced, culturally Muslim, refugee family, with many restrictions and limitations socially and structurally, art afforded me an alternative option to freedom, a safe space of explorative expression without major fear of judgment or punishment – a platform for my needs to land.

Through the physical act of art-making, a different kind of personal therapy can be accessed and this became a way for me to make sense of the complexities of this multi-layered world. As a woman of many challenged and intersecting realities, my practice offers me a tool to look deeper into what human behavior and intersectionality do. I lead with my emotions and navigate life through my art-making.

3. In your photography series Omanis Under Water, you used water as a lens through which to examine Omani culture and society, could you speak more about this piece conceptually.

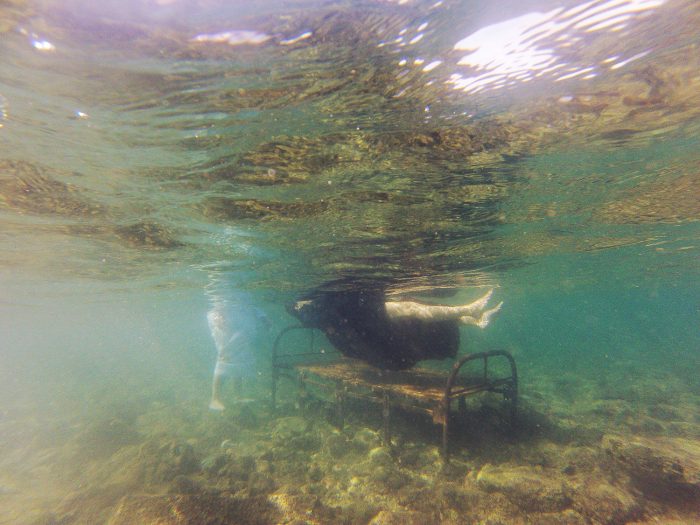

As a concept, Omanis Under Water turns the camera lens underwater to reveal stories silenced and people hidden on land. While water typically distorts light and sound, in this project it acts as a clarifying prism: it draws out the elements of humanity (and inhumanity) that make up a uniformed society, whilst using local participants, subjects and bodies of water.

This concept has allowed me to encourage challenging conversations through beauty, allowing the images to engage with the viewer and soften deeper, and often heavier conversations.. It is a process that has reminded me that everyone needs a safe space to express their reality as we all have something hidden.

In a place like the Middle East, many are afraid to speak their truth, especially when it comes to women and minority groups. In the project, water is both a conduit and protector of truth. Subject’s heads are always kept above water to conceal their identity. This facelessness both protects the subject, keeping the personal but removing the individual threats, and allows the viewer, regardless of ethnicity or gender, the potential to place themselves as the subject.

4. What are your thoughts on the present relationship between world cultures and the earth? How do you hope to use your art to continue shaping this relationship?

This is a big question, one which could have so many different answers. It’s no surprise that climate change is real and our knock-on effects of it even more real. The ‘west’ and ‘developed’ countries need to take a lot more responsibility for their footprints in this reality. Globally, I think what we lack is a sense of personal cultural responsibility, both to the lands, and seas, and to the people who inhabit them now, and in the future.

With this in mind, due to the success of Omanis Under Water, I’ve been developing the project into a much larger and ambitious project called World Under Water which aims to do exactly what was done in Oman but on a global level. It’s a long term project and the second edition of this began in 2018 where I started Brazilians Under Water whilst being based in Bahia, Brazil. Here, like in Oman, I was looking at the silenced socio-political realities of Brazil. Although it’s waters and people are so different from Oman, it shares much in common in regards to stories and social constructs. Furthermore, there too, the water, so turbulent, often unclear and in constant motion, emerges as a metaphor for the politics of the land.

The similarities which emerged between these two projects allowed me to realize the depth of potential for World Under Water to become a survey of all the different bodies of water and social-political realities it can have access to. I’d like to think with projects such as this, the potential for understanding, engagement, and honest exchange can thrive, despite our politically disjointed world. Especially when we realize that all lands and people, scattered across this earth, are united by one Ocean.

To explore more of Estabrak’s work explore the links below.

Website: www.estabrak.org

Instagram: @rough_silk

Author: Carola Dixon